How strange that one of Upminster’s finest houses, Sir James Esdaile’s New Place built around 1775, fell into poor repair and was demolished in 1924, while the adjacent stable block survives to this day? And that after New Place was demolished the panelling, doors and fireplaces from one of the rooms may have been shipped to America where they may still be seen?

Although many of Upminster’s larger houses were bought as country retreats in the 17th and 18th centuries by rich London citizens this wasn’t how Sir James Esdaile (1714-1793) came to own Upminster’s New Place. Esdaile became the owner of New Place through his second wife Mary Mayor, whom he had married in 1748. Mary, the daughter of John Mayor, lorimer of London, was just 17 when she married the 34-year-old James Esdaile. As part of her marriage settlement her childless uncle & aunt Joseph & Sarah Mayor generously endowed her with New Place in Upminster and other freehold land in Hornchurch. After Joseph and Sarah Mayor died in 1755 and 1757 respectively these estates passed to Mary Esdaile.

Sarah Mayor had been an heiress in her own right. Before marrying Joseph Mayor, she had been married (as Sarah Clarke) to John Rayley “late of Queen Street, London but now of Upminster” and when he died in 1718 he bequeathed to her not only all his properties in Upminster (which included New Place) but also the right to dispose of these by her will or otherwise, which is what happened. It had been John Rayley’s father, also named John Rayley, a citizen and draper of London who had died and was buried at Upminster in 1706, who had bought New Place in 1677 from Thomas Hewett. John Rayley senior’s widow Hester seems to have remained at New Place until her death in 1724. Their son in law James Knapton, a well-known London bookseller, also have lived at New Place with his sister-in-law, and he was buried in a large tomb in Upminster churchyard in 1736, as was his second wife Dorothy in 1744.

The New Place residence that James and Mary Esdaile inherited possibly dated back to the Tudor era. Archaeological excavations in July 2010 on the site of Numbers 240 to 242 St Mary’s Lane uncovered the foundations of the original New Place which revealed a large brick-built house of the late 16th century or a little later which was sited some 4m or 5m back from the modern street frontage in St Mary’s Lane to the west of the Clockhouse. Ralph Latham, who also owned the manors of Upminster Hall and Gaynes, also owned New Place on his death in 1557 so he or one of his descendants may have built the Tudor house.

Extract from Archaeological Excavation & Monitoring Report (Field Archaeology Unit, Essex County Council July 2010 )

Sir James Esdaile, who was knighted in 1766, the same year that he was elected as one of the Sheriffs of the City of London, built a country mansion that reflected his enhanced status. New Place may have come to him through his wife’s family but Esdaile also had considerable income of his own from his business in Bunhill Row, after his father’s death in 1758.

Champion Branfill, writing to the Essex historian William Holman in 1720, stated that the earlier New Place had been demolished, stating that “nothing standing but ye outhouses where ye person that now enjoys it dwells”. Before 1775 Sir James Esdaile built a grand new mansion to the south of the previous residence with the entrance drive covering the former footprint. The new house was built of red brick like its predecessor and was rectangular in shape on three stories with single story wings on each side. The west wing accommodated a large saloon which Esdaile, who was fond of dancing, built to hold balls, as there wasn’t a ballroom large enough in the neighbourhood. This saloon was described in 1839 as being 35 feet by 25 feet with 14 feet high ceilings with “wainscot floor, carved and gilt mouldings, stucco cornice, and enrichments”. There were also several fine mirrors while over the mantel hung a portrait of Sir James in Court dress. The ground floor also housed a library (16’ by 14’), a dining room, 22’ by 14’, an ante drawing room, 20’ by 14’ 6” while on the first floor there were three bedrooms, addressing rooms and closets, with five bedrooms, a dressing room and closets on the upper story.

After Sir James Esdaile died on 6th April 1793, New Place passed to his eldest son Peter (1743-1817) and a sad incident occurred on 16th January 1812 when Peter’s 59-year-old younger brother James shot himself in the grounds of New Place. The New Place estate remained in the Esdaile family until 1839 when it was bought at auction by James Harmer (1777–1853), alderman of London and owner of the Weekly Dispatch, and from there it descended to the Umfreville family, who eventually sold the house & 65-acre estate to W P Griggs & Co. in 1909. After the sale in 1839 the house and estate was leased to tenants, one of whom Capt Richard Pelly RN, almost completely rebuilt the east wing after he came there in 1867, adding a story to provide more room for his growing family of six, plus as many live-in servants and replacing the former entrance gates.

New Place from front entrance c.1912

The final occupier, from the late 1890s was John Wilson, Chief Operating Engineer for the Great Eastern Railway and his family. A survey in 1912 stated that “The mansion is old & very considerably out of repair, too large for the immediate district & will probably be pulled down”. In fact it survived for 12 more years for when Griggs & Co acquired the whole estate in 1909 they allowed Wilson to continue to occupy the premises, although the company began developing the area around the house and gardens as the New Place Estate, starting with Argyle Gardens in late 1920. The memoire “Happy Memories of New Place” by Muriel Sharp (1908-2001), John Wilson’s granddaughter, dates from this period of the final days of this fine old country house. Among her memories was “the drawing room, which … was originally the ballroom of the house built by Sir James Esdaile. It had an Adam fireplace and in each corner of the ceiling was a cornice of Aesop’s fable of the fox and the grapes”.

John Wilson died in November 1922 and his widow Emily gave up possession in March 1923. This led to much speculation and a protracted local debate and consultations about the future of the house. By mid-June 1924 all attempts to save the building had been exhausted and it seems the run-down old house was demolished shortly afterwards. In August 1923 notices were published advising of a sale by auction on 11 September of building materials and other remnants from the house, which included window frames, doors, “marble and slate fireplaces and grates”, and “Portland stone cornices”.

The fashion in salvaging and buying period rooms and shipping them across the Atlantic was common in the 1920s, when many stately homes were being demolished. In 1925 or 1926 one of the leading London dealers in this trade Roberson’s included details in thri trade catalogue of two panelled rooms said to be from from New Place.

Around this time Edsel Ford, son of Henry Ford and an executive of the Ford Motor Company, and his wife Eleanor were building a mansion in Grosse Point Shores, northeast of Michigan, on the shore of Lake St Clair. They engaged an expert interior designer to fit it out with antique wood panelling and other fittings brought from a variety of old English manor houses. One of these rooms, the dining room at Edsel and Eleanor Ford’s home, was undoubtedly purchased from Roberson’s whose brochure described this as “The Pine Room from The Clockhouse, Upminster sometimes called The Treaty House”. It has been pointed out the New Place was never known as the “Treaty House” and that it’s possible that Roberson’s confused this with the Treaty House in Uxbridge, rooms from which were offered for sale by Roberson’s in the late 1920s.

There is another contender for a room from New Place which was relocated to the USA. This is a drawing room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art which was purchased in 1926 from another London dealer White Allom. It was installed as part of the museum when it reopened in new premises in 1 April 1928 and it was then said to be from “The Treaty House in Upminster”. However, a British expert (John Harris author of Moving Rooms: the trade in architectural salvages – 2007) casts doubt on this. One factor is that the style of the Philadelphia room is much earlier than New Place, dating from the 1740s. A further, particular concern is that Ernest E Newton, a distinguished local historian who had lived in St Marty’s Lane opposite New Place from around 1911 and was a key figure in the attempts to save the house, wrote to the Philadelphia Museum in March 1930 pointing out that the house had never been known as “The Treaty House” and saying “I do not remember ever seeing any old panelling in the house, although there may have been some covered with paint or paper, but when the house was sold, it was said that a lot of material was put into the sale which never belonged to New Place at any time.”

The room is still on display at the Museum, where it is described as “Drawing Room, possibly from New Place”. As can be seen from the picture below this bears no resemblance to the actual drawing room at New Place, Esdaile’s former ballroom. The jury is therefore out on whether the ey features of the Philadelphia room originated from New Place.

Drawing Room from the Philadelphia Museum of Art: which may be from New Place (Credit: Gift of William M. Elkins in memory of his father, George W. Elkins, 1926, 1926-78-1)

New Place’s coach and stable block, which in 1839 had contained two coach houses, a four stall and a two-stall stable with hay loft and a loose stable for three horses, survived. It’s not hard to see why because on the roof Esdaile added an octagonal clock turret with an ogee dome and weather vane brought from the Woolwich Arsenal housing a large clock, built in 1774 by the famous London clock maker Edward Tutet, Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in 1786, three years before his death. In an age where it was rare for people to own a timepiece, this village clock provided the people of Upminster with their only public timepiece. Wilson’s 1856 history called it the “great” or “village clock” and by 1881 the house itself had become known as “Clockhouse” and the road outside, now St Mary’s Lane but then Cranham Lane, was often known as “Clockhouse Lane”.

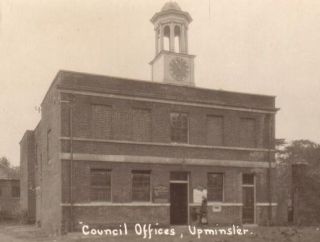

Clockhouse – c.1920s after it was bought by Upminster Parish Council

The debate over the future of the Clockhouse extended over many months during 1923 and 1924 and it was only at the end of that year that the parish council was able to go ahead with the purchase for £1,130 and alterations. These changes allowed the building to serve as an office for the parish clerk Albert Briebach who had for almost 15 years operated out of the front room of his house in Gaynes Road, and as a store for the parish fire appliance – at that time still a hand-truck. When Upminster became part of the Hornchurch Urban District Council in 1934 the parish no longer needed these premises and two years later Clockhouse was converted to house Upminster’s first library – which it remained until the current library opened in Corbets Tey Road in 1963. Once again the future of Clockhouse lay in the balance as there was no obvious use for the 200 year old building. However, once again local opinion prevented its demolition by Havering Council demolishing. The listing of Clockhouse in 1972 ensured that the threat to its future was lessened and it is still in use 45 years later as residential accommodation.

The Clockhouse was – and of course still is – also noted for its grounds which originally extended to almost six acres around the house. Muriel Sharp’s memoire (mentioned above) recalls the gardens around a hundred years ago including the shady shrubbery walk which ran west right along the northern boundary of the estate towards Corbets Tey Road. This emerged through a gate to the south of the Bell Inn opposite St Laurence’s Church – one of the original gateposts still survives at the Upminster Infant School entrance. This walk allowed the owners of New Place uninterrupted access to their private chapel at St Laurence’s Church, the St Mary’s or Lady Chapel completely rebuilt in 1771 by Sir James Esdaile who also added a family vault for his family to be buried in, as had former owners of New Place.

Clockhouse Gardens – around 1950

The grounds had largely become a wilderness in the years after the demolition of New Place and it was only in 1938 that work started to convert these into a public park and Clockhouse Gardens opened in the summer of 1939. The gardens therefore celebrated the 75th anniversary of their opening in 2014.

Pingback: Who was Sir James Esdaile? | Old Upminster

Pingback: A walk down Corbets Tey Road | Old Upminster

Pingback: The Road to Cranham – Part 1 South Side | Old Upminster

Pingback: St Mary’s Lane, North side: Part 2 – from Garbutt Road to the Cosy Corner Crossroads | Old Upminster

Pingback: The Bell Inn | Old Upminster

Pingback: Upminster’s Cosy Corner (137 St Mary’s Lane) | Old Upminster

The paneling that was taken to Edsel Ford’s mansion now resides in the Museum of Fine Art in Philadelphia. You can’t imagine what an old Brit felt like when she entered the room which displayed the paneling from New Place as she was born and lived for a few months near New Place then went up to River Drive and later to Canada. After eight countries more she was dumped in West Chester, Pa. but regularly visits the museum in Philadelphia. So now you know where the paneling ended up. Aileen amfkennedy37@gmail.com

Actually, the paneling that was taken to Edsel and Eleanor Ford’s home is still there and intact- just like the photograph in this article shows. The home is open for public tours from April thru December and the docents all mention the origin of the paneling giving credit to Clockhouse and Upminster.

Pingback: Upminster in Living Memory Revisited | Old Upminster